Simpler Times

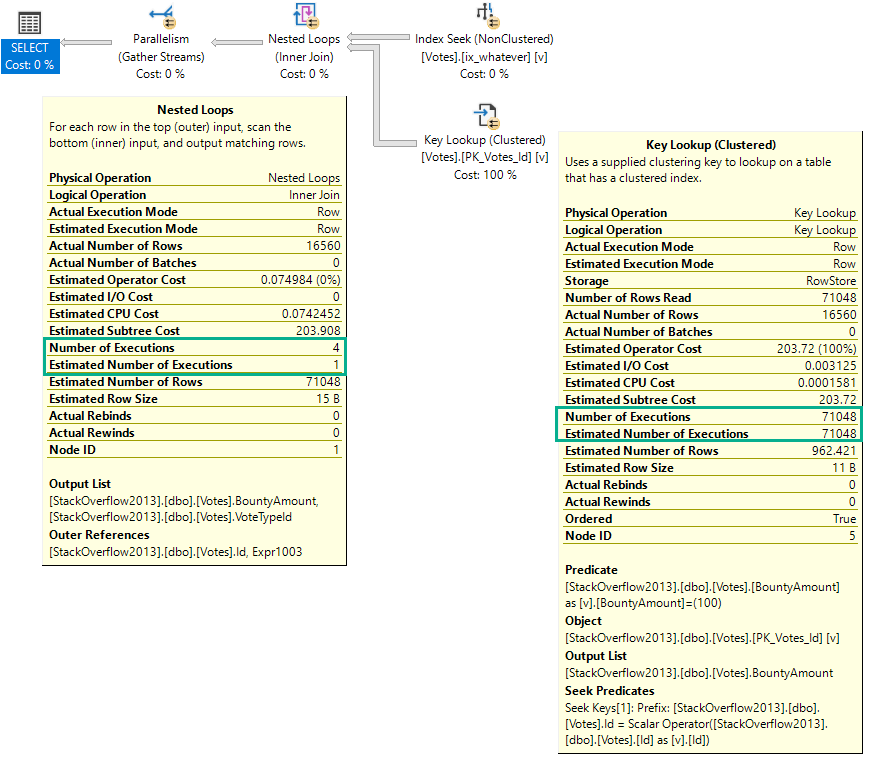

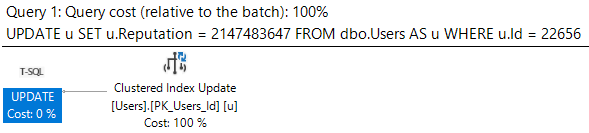

Let’s say we’ve got a simple update query. When we run it, it finishes instantly, and the query plan has no surprises.

BEGIN TRAN UPDATE u SET u.Reputation = 2147483647 FROM dbo.Users AS u WHERE u.Id = 22656; ROLLBACK

Then one day DevOps comes along and says that every time Reputation gets updated in the Users table, we have to check a bunch of conditions and then do a bunch of stuff based on the value.

One of those checks is to see if anyone has the ?INT MAX? and then insert a row into Badges.

Because I’m lazy (Agile?), I’m going to stick a waitfor in the trigger to simulate all the other checks and actions.

CREATE OR ALTER TRIGGER dbo.one_time

ON dbo.Users

AFTER UPDATE

AS

BEGIN

IF EXISTS ( SELECT 1/0

FROM Inserted

WHERE Inserted.Reputation = 2147483647 )

INSERT dbo.Badges ( Name, UserId, Date )

SELECT N'INT MAX OMG', Id, GETDATE()

FROM Inserted

WAITFOR DELAY '00:00:10.000'

END;

GO

Less Simpler Times

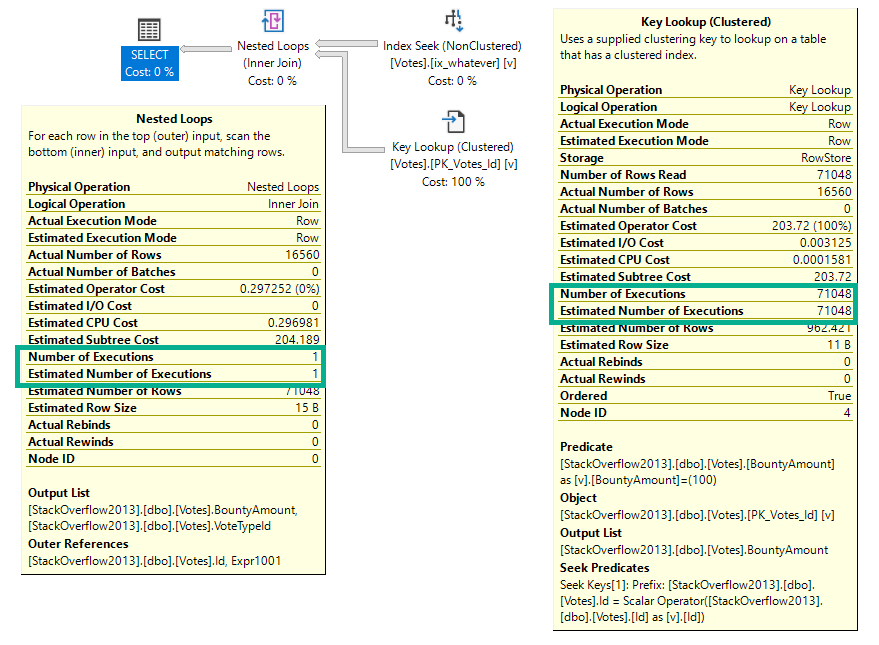

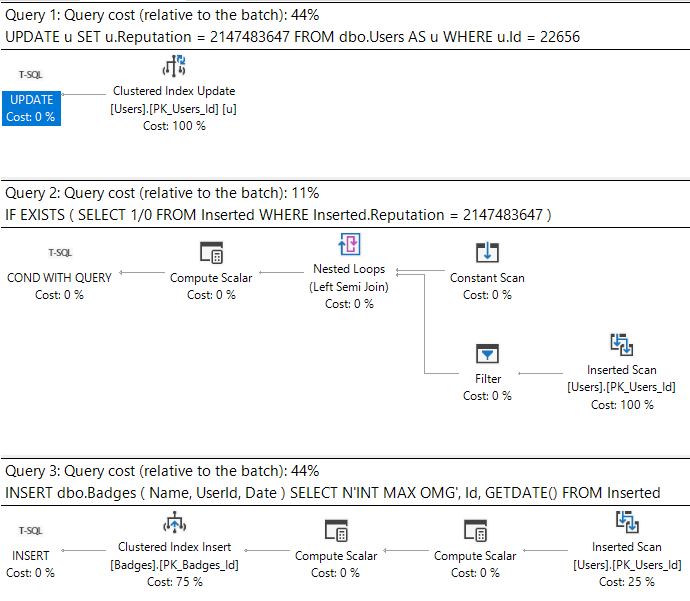

Now when we run our update, the plan looks like this.

What’s important here is that we can see the work associated with the triggers.

What sucks is when we look at the plan cache.

Back To Easy

I’m gonna stick that update in a stored procedure to make life a little easier when we go looking for it.

CREATE PROCEDURE dbo.update_reputation

AS

BEGIN

BEGIN TRAN

UPDATE u

SET u.Reputation = 2147483647

FROM dbo.Users AS u

WHERE u.Id = 22656;

ROLLBACK

END;

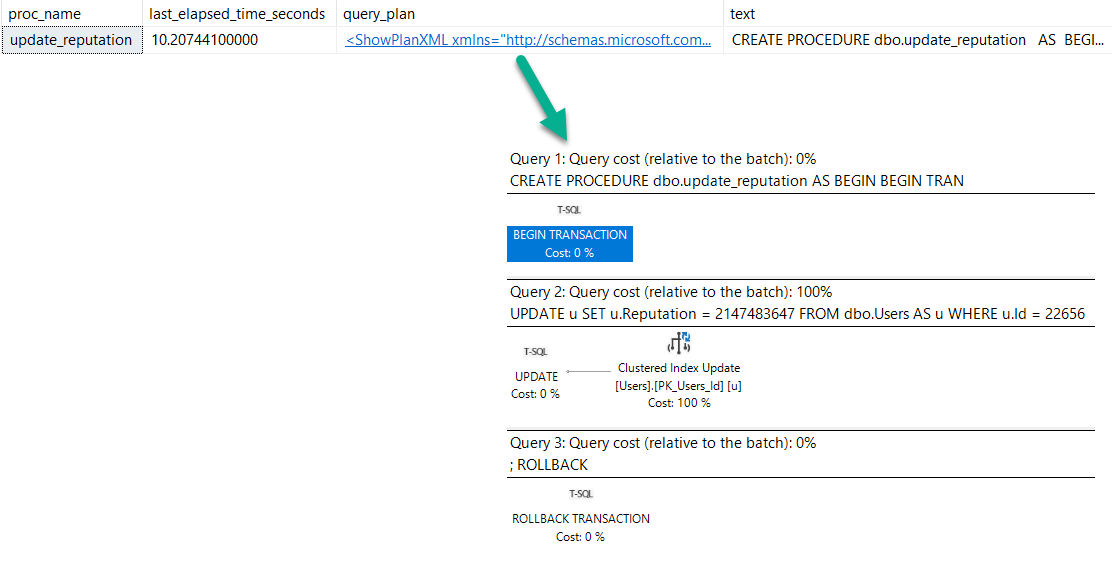

After running the proc, here’s what we get back from the plan cache.

SELECT OBJECT_NAME(deps.object_id) AS proc_name,

deps.last_elapsed_time / 1000. / 1000. AS last_elapsed_time_seconds,

deqp.query_plan,

dest.text

FROM sys.dm_exec_procedure_stats AS deps

CROSS APPLY sys.dm_exec_query_plan(deps.plan_handle) AS deqp

CROSS APPLY sys.dm_exec_sql_text(deps.plan_handle) AS dest

WHERE deps.object_id = OBJECT_ID('dbo.update_reputation');

We have a procedure reporting that it ran for 10 seconds (which it did, sort of…).

But no mention of the trigger. Hm.

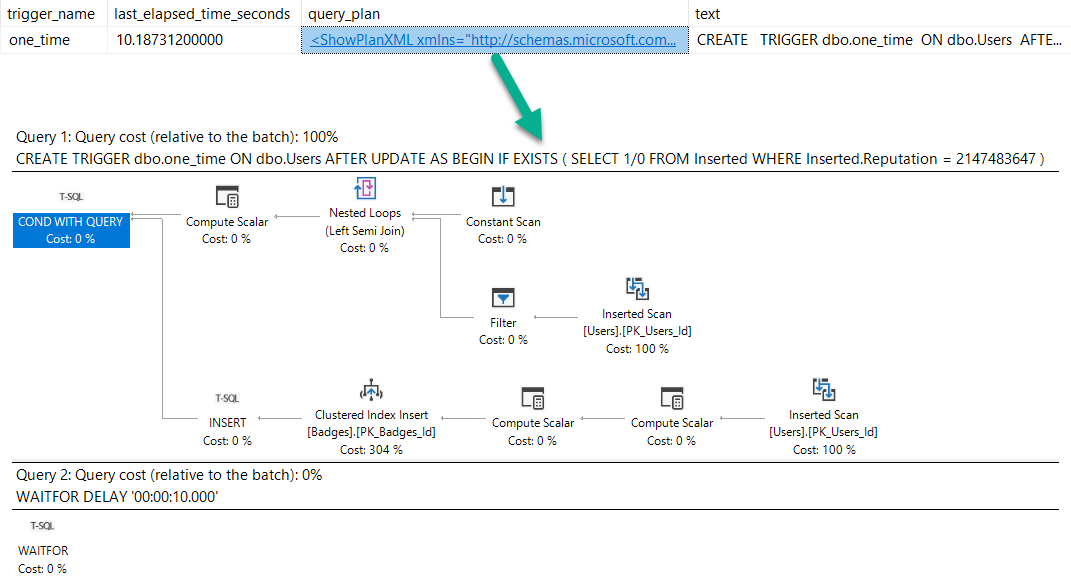

Of course, we can get this information from trigger stats, but we’d have to know to go looking:

SELECT OBJECT_NAME(object_id) AS trigger_name,

dets.last_elapsed_time / 1000. / 1000. AS last_elapsed_time_seconds,

deqp.query_plan,

dest.text

FROM sys.dm_exec_trigger_stats AS dets

CROSS APPLY sys.dm_exec_query_plan(dets.plan_handle) AS deqp

CROSS APPLY sys.dm_exec_sql_text(dets.plan_handle) AS dest

WHERE OBJECT_ID = OBJECT_ID('dbo.one_time');

Lying Liars

When seemingly simple modification queries take a long time, things may not be as simple as they appear.

Blocking, and triggers might be at play. Unfortunately, there’s not a great way of linking any of that together right now.

Thanks for reading!

Going Further

If this is the kind of SQL Server stuff you love learning about, you’ll love my training. I’m offering a 75% discount to my blog readers if you click from here. I’m also available for consulting if you just don’t have time for that and need to solve performance problems quickly.